‘He who fears he shall suffer, already suffers what he fears.’

Michel de Montaigne

The appointment was routine enough.

An ancient wisdom tooth had been grumbling and crumbling away at the back of my mouth for some time. At my last check up, I’d been told I’d be better off without it and it was time to follow through…

The dentist gave me Novocaine, doing her best to hide the huge needle below my sightline as she prepared to strike, though my imagination managed to conjure the cartoon shadow on the white wall. Then she went to work. I felt no pain, only the squeaky tugging of tiny roots clinging to gums that had been their home for decades. When the tooth finally came loose, she put it on the tray in front of me and pointed to a thin black ring once hidden behind my receding gums. ‘Bacteria’, she said. I tried to muster the appropriate response through lips still numb and with a wodge of cotton clamped between my remaining teeth to stem the bleeding.

I left the surgery feeling bruised but relieved the ordeal was over. That night an abscess developed on the roof of my mouth and grew to the size and shape of a kidney bean. Some time in the early hours of Sunday morning, the abscess must have burst, and by the time I saw the dentist again, the kidney bean was no more than a flap of raw skin, and the pain had gone. She insisted on X-rays to make sure there was no underlying cause. There was. She found an enormous cavity, hidden between two teeth, and worse, worrying signs that the bone of my jaw was eroding. Thus began a series of expensive and often uncomfortable treatments that are not entirely over yet, and a warning that unless I control the downhill slide in my teeth, and cap those that are too far gone, I am likely to lose them all in the not too distant future.

Harsh news though nothing out of the ordinary for a man of my age, and yet it hit me hard. Too hard. I determined to pull myself together and I fully expected my low mood would go as quickly as it had come. But a few weeks later, when the cavity had been filled and the gaps in my lower gums excavated with a surprisingly painful water jet, I was still listless and morose.

If I was making a mountain out of a molehill – and I was – it seemed I’d been tripping over a lot of molehills recently. Varicose veins on the calf of my left leg that made me limp for the first few hours of every day, and arthritis in my little finger that was sore, especially in the winter. I had a knee that clicked and a lump on my back that might be growing, I didn’t dare look. All thoroughly minor ailments and par for the course, so why was I taking it all so personally? It was not depression, though it seemed that way to those close to me. They sensed my absence, circling and soothing me with their quizzical love, and I was sorry for them, more so than for myself. But I didn’t feel low, so much as panicked.

Others had real mountains to climb. A friend and colleague, a man who gave me opportunities beyond my talents, a man I hadn’t seen for some years, wrote a serene email to tell me of his terminal diagnosis. For a week or two, that humbled me and put my indulgence in nebulous fear to shame. We’ve met for lunch more often since, and I’m glad we do. Another, my former editor and a dear man, has kept me up to date on a long series of operations that seemed to go on forever. And just three months ago, Phil, my best friend in the world and a man I’ve know for more than forty-five years, called to tell me he had cancer of the oesophagus. That floored me, not least because I’d been staying with him at his home in France until the day he went to the hospital for the tests. When he dropped me off at the airport for my return flight, I’d wished him luck and told him not to worry. I said it was probably indigestion.

If nothing was seriously wrong with me, what on earth was wrong with me? People important to me were facing challenges with courage. And here was I, without a scratch on me, feeling the walls were closing in and wanting to run for the hills, if that’s not one metaphor too far. I began to wonder if I was not simply drowning in my own gene pool. My father’s generalised anxiety disorder might just be playing out in the next generation. He saw danger everywhere, and yet despite the locks on the doors and the halogen security lights all around their suburban bungalow – the house where my sister and I now care for our mother together – the threat he’d been so vigilant in guarding against had crept unseen into his own home. My mother’s Parkinson’s dementia was impossible for him to cope with or accept. Seeing his hard-earned savings flying out the door in care costs undermined everything he had strived for in his life. Fear killed him, and now I had reached my sixties, a time when I remember him beginning to show signs of an all-encompassing anxiety, fear was stalking me.

Then, a still more shocking idea struck me. Perhaps this was nothing more or less than a long delayed mid-life crisis. With others going through real wars, the banality of this explanation shocked me. And yet I had the symptoms. I know, because I looked them up online:

- Feeling sad or a lack of confidence

- Loss of meaning or purpose in life.

- Feelings of nostalgia.

- Impulsive actions.

- Feelings of regret.

Surely a mid-life crisis in your sixties stretches the definition to absurd lengths. Was there not such a thing as a ‘nearing-the-end-of-life crisis’? That would make more sense, particularly when set against the backdrop of the ‘nearing-the-end-of-the-world’ crisis going on all around us. As I write, the wars in Europe and elsewhere are killing thousands of innocents every day. Millions lost their lives to the pandemic. All of us are threatened by a climate catastrophe. And yet our generation is hardly the first to experience tragedy on a global scale. W.B. Yeats wrote one of his most famous poems, The Second Coming, only a year after the end of the First World War. This famous couplet was relevant then, and resonates today:

‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.’

I see people full of passionate intensity today; I see politicians telling lies on the television in a post-truth world where it’s expected they will lie and get away with it. I see demagogues with easy answers to difficult times that pit us one against another. And I see the rest of us, bewildered, lacking all conviction and burying our heads in our phones hoping to find answers there. We live in an age where fake news is the only certainty and echo chambers the only safe place to hide. This is indeed a pitiless world with existential threats we can do little to ameliorate.

Anhedonia is a word I only discovered very recently. It was coined by a French psychologist, Théodule-Armand Ribot, in 1896, and originally meant ‘a reduced ability to experience pleasure.’ More recently, it has come to mean a lack of motivation to want, or like, or do anything very much. AI, together with climate change, wars, and pandemics, will do that to you and many of us are experiencing something like a debilitating feeling of resignation in the face of such overwhelming odds. I confess I shamelessly called upon these crises as cover story for my own state of mind. What’s worse, the strategy worked – for a time. I even believed it myself. Though only for a time.

If the state of the world mirrored my own, one did not cause the other, though it did nothing to help. Instead, my tiny crisis was just a scintilla of distress to add to the great mass of distress in the wider world. In my defence, all I can say is that once I realised I was guilty of subterfuge, I kept up the facade only in order to buy the time I needed to fix myself.

But I failed to fix myself. And though I don’t remember a particular moment in time or a day when it happened, but I began to dread another call from another friend with another ailment I could do nothing about, except to listen. I began to dread another symptom in my own body’s ageing process, with no particular cause and no particular remedy, just another thing to add to the list. I had palpitations at odd times and for no particular reason. The bags under my eyes were there every morning now, regardless of the quality of sleep the night before, and my insomnia became so chronic that I dreaded going to bed. I forgot why I went into rooms, and wondered if my mother’s dementia might play out alongside my father’s anxiety in a double-whammy, only to realise I was now in the land of frenzy. I wanted to stay under the duvet in the mornings. I dropped things, a lot and for no reason. I wanted to weep, at almost anything. Sentimental films and the news became a no-no. Only then did the coup de grâce of my teeth bring me low. Only then did I fully appreciate that, ‘The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to,’ had crept up on me too, thieves in the night, stealing a little here and a little there, depleting my reserves of courage, insignificant as they were, until there was nothing left.

I had thought I would do better. Better than my dad, and better than I am doing. I had imagined myself clear-sighted and calm at this age. Over the years, I’d read bits of Hellenistic philosophy, the Stoics and the Epicureans particularly, and the Skeptics. I’d even begun to imagine some of their wisdom might have stuck. I’d dabbled in Zen Buddhism, with the usual suspects, Thích Nhất Hạnh and Shunryū Suzuki. I had tried to get to grips with the Tao – about which all I could really glean was that ‘striving’ of any kind was generally not a good thing. And I had found Michel de Montaigne, who when faced with his own dental crisis in later life had this to say:

‘I have one tooth lately fallen out without drawing and without pain: it was the natural term of its duration…’tis so I melt and steal away from myself.’

Michel de Montaigne, Essais, Chapter XIII, Of Experience

Any wisdom I might have claimed had gone the way of my eponymous tooth, and yet here was someone who could bridge the centuries between us and make me laugh:

‘God is favorable to those whom he makes to die by degrees; ’tis the only benefit of old age; the last death will be so much the less painful; it will kill but a quarter of a man or but half a one at most.’

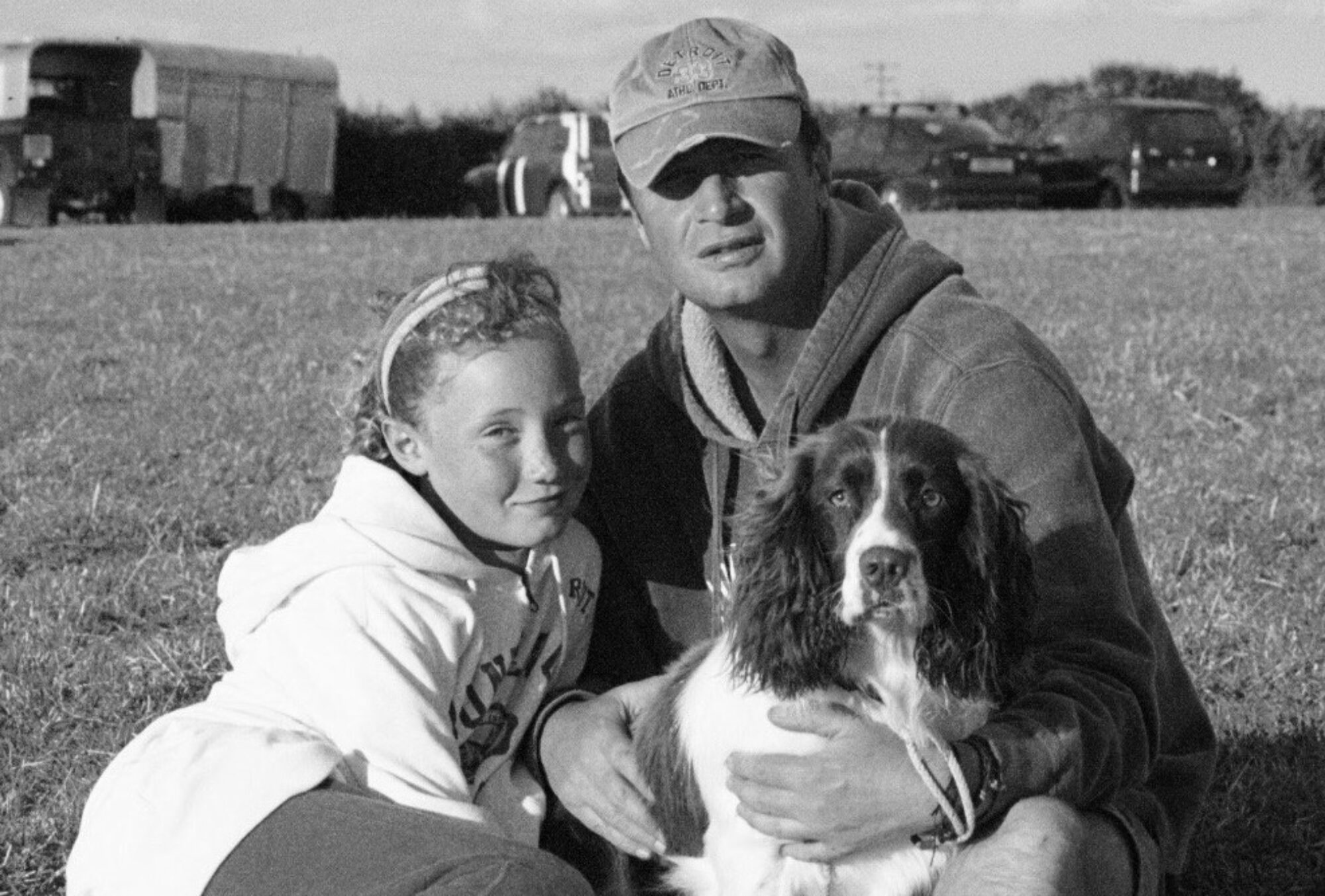

But to philosophise, even with a smile, is not to live. I needed something more, a complete break and an opportunity to stand back from myself and my life. My sister said I was simply worn out. She said seven years of caring for our mother, and two years of regular lockdowns at the height of the pandemic, had left me exhausted and brittle. She told me I must pursue the idea of the bike trip and put plans in place immediately. When the notion of my daughters coming with me for a few days was added to the mix, and they agreed, there was no going back.