An excerpt from Love and Care, the book…where you can read about a very special a beach walk with my dad…

An excerpt from Love and Care, the book…where you can read about a very special a beach walk with my dad…

‘Beautiful,’ says Kate Mosse of the book. ‘Candid and funny,’ says Raynor Winn. Tony Parsons: ‘A superbly honest memoir about the unbreakable bonds of family.’

The summer seems to have come and almost gone before I’ve really had a chance to fulfil my promise to myself that I would make time for…you guessed it…me.

What a horrid old cliché that is…time for me? And yet it’s something many of us fervently wish for but seldom get. What it amounts to is really just a series of days, weeks or months if you’re lucky, where not very much happens, and especially where very little goes wrong.

I thought this summer might be like that, partly because so much had happened, not all of it good by any means, in the months leading up to a very sunny June. But alas, it was not to be. When you’re young, you imagine there’s a time in the future where the fray will be done, the striving over, and a calm will descend on a perfected existence, after children and with plenty of money to spend on whatever whim takes your fancy.

When you’re old, as I am now – quite suddenly and unexpectedly – you realise that no such place exists. There is no nirvana, no plateau, and no mountain high enough to allow you to look down on life untouched by the affairs of a human race that resembles scurrying insects pursuing intangible goals. You’re still in it, up to your neck. Stuff keeps happening, some good, some bad, and the only difference now is that you’re aware of aches and pains in your legs, and remembering what you went into a room for makes you feel like you’ve got it all under control.

One of the reasons I thought I’d earned a break was that, as you know, I’d been writing a book called Love and Care, based on this podcast. What I didn’t know was that writing the book is the easy part, relatively speaking. After it’s in the bookshops, comes the hard bit, with publishers and agents keen to get you out there to sell the book. I’m not a tweeter, but I had to have a Twitter account, or is it called X now? And if it is, who really cares. I have a Facebook account, but only because I was asked to have one. I can’t say I use if for anything productive. In fact I seldom look at it, and it seems to me, that like texts, Facebook is most useful for birthdays you’ve forgotten and buying things without paying Ebay for the privilege.

Though one rather exciting prospect has appeared, I am appearing as myself to be interviewed at the Jersey Festival of Words. Chris Stone, who works for the local radio station, has the difficult job of making me seem interesting, and I will do my best to assist in any way I can.

Anyway, the point is acres of time go by, hence my absence from the airwaves – or pod waves – for which I can only apologise, and try to make amends by reading an extract, so allowing a glimpse of the whole story. Though I might hold the end back in order to allow a little dramatic tension. At least for now.

We’re driving to the airport, again. My sister is at the wheel and I’m the passenger. She’s squinting in the glare of winter sun on wet roads and leaning forward in her seat, still getting used to driving on the left after a lifetime in north America. So I hesitate before I ask her, ‘Are you sure you’re okay with this, Sis? You don’t mind that I’m going to Ireland … and without you?’

‘I’m fine with it if you are

‘You have to do this, for you. Isn’t that what you said?’

‘But it’s Christmas Eve tomorrow, and with the family coming …’ ‘Look, the prep is done. We’ve got the turkey, that’s all that was worrying me, and there’s a whole wine cellar in the garage now. Stop worrying.’

‘And Phil?’

‘He can have your bed tonight and the floor tomorrow. We’ll raise a glass tonight. Like I said, stop worrying. Have you got everything?’

‘It’s just Dad and me, and a toothbrush.’

When she drops me at the terminal, I take the wheelie bag and kiss her goodbye. She looks rueful, but says nothing. I go to the desk to check in, and I’m still wondering about putting the bag in the hold, even though it’s fine as carry-on. There’s no customs, but there is security to think about, and I’m just not sure I want to explain exactly what I’m taking with me in this case, alongside a change of clothes and a wash kit. In the end, I keep the bag with me and I’m relieved when it trundles through the scanner just fine and security let me pass without grabbing me by the arms.

I while away the time until the flight is called in the bookshop. Every time I fly, I browse the shelves for my book, hoping to find it nestling amongst the top ten bestsellers. I’ve yet to find it there, maybe they’ve sold out I think, without telling anyone else I think like that, but I suspect other authors do the same. I don’t feel inclined to buy anything, not even a newspaper. After all, the flight is only an hour and a half, and having been landlocked for so long, I can spend my time looking out the window at the Irish Sea below and maybe treat myself to a beer or a gin and tonic with the money I’ve saved.

We land in Derry to wind and rain, but then it is December. I know there’s a bus that will take me up the coast towards Tullagh Strand, but nothing that will go all the way, so I’ve elected to splash out on a hire car for the forty-minute road trip north to the coast. I had a fantasy I might hire a taxi to take me there, but the chances of meeting a real-life Paddy Reilly seemed remote and a tad romantic. I’ve booked a room at the Railway Tavern in Fahan because they have traditional music and an open fire. I’ll need to warm my bones after such a day, and besides, I’m a tourist in Ireland despite my newly acquired Irish passport. I filled in the paperwork before Brexit, just as a precaution, and back it came six weeks later. When I realized that Dad’s heritage allowed me the privilege of being a European still, I thought, why not? Though I knew I wouldn’t have to show it, I have it with me, just because I like the idea.

Derry airport is small and the hire car is waiting for me. I follow signs to the city and cross the Foyle river to head along the Donegal coast towards Muff and Quigley’s Point before cutting inland and across to Tullagh Strand, a horseshoe bay with a gorgeous beach that I picked out from the map simply because it had the word ‘strand’ in the name. I can picture the scene of the woman calling to her man in the story that Dad used to tell. I don’t know how to find the place where he was born, or where he went to school. His birth certificate names a village near Strabane in the North, but that’s not why I’m here. It’s not roots I’m after. I only hope that my choice is the right one.

The countryside around me is brown heath as far as the eye can see, and there are no trees, just sky, vast and glowering, with weighty clouds in shades of grey with only the very briefest breaks. Houses give way to bungalows that crouch and hide from the wind. Ireland seems to me a land of bungalows, especially in the wilder parts. Many are new, with plastic windows, practical but downright ugly, and soon after Clonmany, with only a couple of miles to the beach, there are mobile homes that are uglier still.

I park up at the furthest end of the beach because there is a view of Súil Rock Binnion, which I read means ‘the eye of the rock’, though I don’t feel I am being watched. There are few foolhardy enough to be here at this time of year, the day before Christmas Eve with a brisk wind coming off the North Atlantic, though I can see figures in the far distance walking the sands. I have to say, it is beautiful, and desolate too. Perhaps I chose right after all.

Though as I unzip the wheelie bag and take out the green plastic jar, the wind pulling at the door, I wonder if I am completely crazy. Thank the gods the Irish family don’t know what I am up to.

It is already four o’clock, and if I am waiting for one of those shafts of sunlight to suddenly appear from the heavens, I might be waiting till spring. This all seemed straightforward in my mind, but now I am here, it has the banality of the real, and there is no epiphany, even when I try to force the feeling.

I pick my way over rocks and seaweed and keep walking until I have sand beneath my feet, clutching the jar with the ashes under one arm, then the other. It has weight to it. When I think I have gone far enough, I set it down on the beach and take a look around. No one. Or no one near enough to make any difference. There may be a couple of people over towards Binnion Rock, but they can’t see much from that distance. Still, I’m embarrassed and not quite sure how to do this. And to think I could have been sunning myself in Varadero, the Caribbean flat calm in front of me, palm trees behind, and a bar on the beach serving cocktails of rum and coconut milk.

Because my father was a singer of songs, it crosses my mind to begin humming or singing out loud. There is no one to hear. I am alone, or alone with him. We never had a deathbed reconciliation; he was too far gone, and we didn’t have the language for it anyway. But here and now, I could say a few words. I could say goodbye, and I could make the effort to remember him properly. That thought stops me in my tracks. What do I remember of the man?

The anger and the anxiety, yes, but that was not the whole of him, and the difficult later years have obscured his better self from me for so long. He had dreams and aspirations, many of which he fulfilled by escaping his upbringing in a loveless household and creating a family and a home of his own. And if his dreams were dashed and he became bitter and disappointed, I wonder now if much of that disappointment was with himself. Perhaps that was why he wanted to push me forward, to mould me in his image and see me succeed where he had failed, like so many fathers.

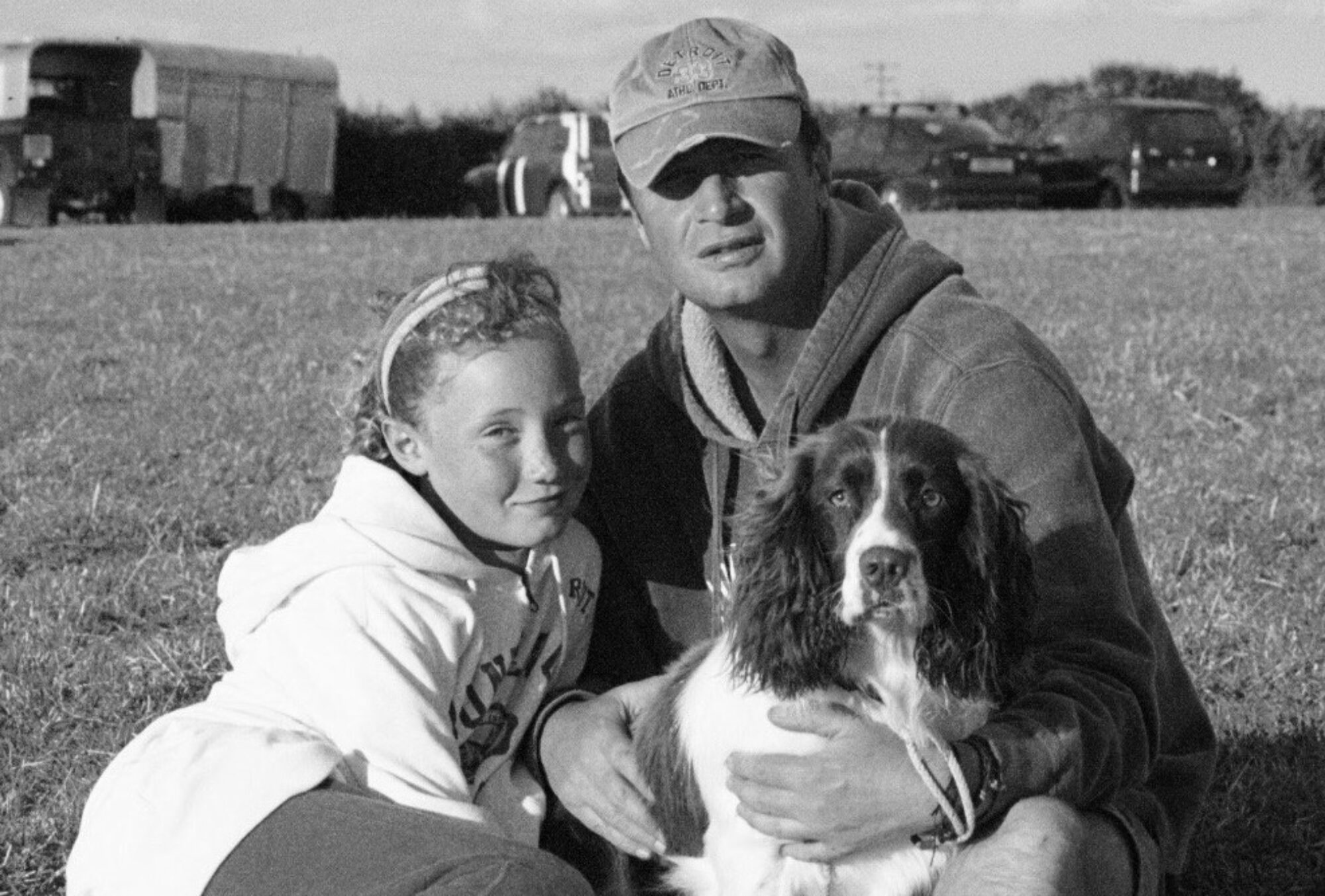

The man I see in the old photographs, kneeling beside his five-year-old son who is blonde-haired and dressed like Rupert Bear, was not angry but proud. The man who spent his Saturdays after a long week at work refereeing football matches for the team he set up for me and my friends in the green strip of Ireland was the good father I have forgotten until now. The man with his arm around Mum, the two of them only in their early thirties, casually close, intimate, easy with each other, as only lovers are, was not anxious but happy and content.

All at once, I see us in the back garden of the old house, kicking a ball around together. The wooden pergola in front of the French windows was the goal. He was the shooter and I was goalie, and if I let one in, from time to time, a pane of glass would shatter and I’d hear my mother call from the kitchen to find out what was going on.

‘Nothing!’ he’d shout back. ‘We’re fine.’ ‘I heard glass breaking,’ Mum would say, leaning out of the kitchen window. ‘Shh!’ he’d say to me, giggling and looking for all the world like a schoolboy himself, then he’d whisper, ‘We’ll fix it later, the two of us.’ And we would. We’d go together to the shop and pick up a new pane, and I can see the tin of putty and the way he’d smooth it with his thumb and a kitchen knife, and show me how, and tell me about the skills I’d need to be a man, and how life was tough and I needed to be tough too. And when it happened again because he kicked the ball too hard or I missed the catch, we’d cut cardboard to cover the missing glass until we could go back to the same shop and buy another pane. That man was not anxious or angry. He was my dad. I don’t know if he can hear me as I stand on the beach with the ashes before me on the sand, mute and inert. But I hope he can, because I have something to say. ‘Do you remember the windows, Dad? I hope you do, because I do. It wasn’t all bad, not all of it, and it wasn’t all your fault. Sometimes I make it sound like it was, but there was other stuff, wasn’t there? I know your dad was pretty tricky, or so your brothers told me. You never wanted to talk about that. Maybe with good reason. We can’t spend our lives blaming our mums and dads for everything, can we?

‘So this is what I wanted to say … I let you down, I know that. I didn’t pick up your mantle as you wanted me to. I didn’t go for the business course in America, I didn’t want to work for the man. I didn’t buy a big house, climb the corporate ladder or join a golf club. And to be honest, I haven’t done much else worthy of note. Sorry about that. But you let me down too, though mostly by being so hard on yourself. Sure, you were hard on me, but we didn’t really get each other, did we? If only you could have accepted my help, leaned on me a bit, things would have been better. But it is what it is, and that’s all ancient history now. That’s why I’m here, that’s why I’ve come to this place. To make peace. Because in our own way, we loved each other, you know? Neither of us was very good at showing it, but that’s down to both of us. Anyway, it’s done. Time now to forgive and be forgiven. Can we do that?’

I wait. My face is wet, though I’m sure it’s the spray, and the only answer is the waves rolling in.

I don’t know what else to do or say, so I pick up the jar and head towards the waterline. The ripples of salt water are running under my shoes, and all at once they wash over and soak my socks. Wellingtons would have been sensible. But I just don’t care, so I go a little further and give the jar a shake. In my mind’s eye, I unscrew the lid and stand back like I’ve lit a firework as I wait for the swirling wind to reach inside and lift the ashes into the air in a magical plume of smoke. Only nothing is happening. The wind isn’t doing what it should. I give the jar another shake and tip it towards the ocean, and all at once the ash is pouring out, sucked into the air, not a plume, but a fog of particles snowing and swirling around my head and landing on my clothes. I don’t want to breathe it in, so I take quick steps backwards holding the jar at arm’s length in front of me, until I stumble and fall, landing on my arse with a splash, feeling the sand sink beneath my weight and the icy sea seeping through to my skin.

Only then, with the empty jar in my lap, do I start laughing.

End.

Written and read by Shaun Deeney

Edited by the same

Music and sound effect credits

Freesound – “Beach Walk” by eqavox https://freesound.org/people/eqavox/sounds/683345/

Freesound – “Ocean Noise – Surf” by amholma https://freesound.org/people/amholma/sounds/372181

Freesound – “Heathrow Airport.WAV” by inchadney https://freesound.org/people/inchadney/sounds/323508/

Freesound – “North Sea at Night at Farnoe/Denmark” by pulswelle https://freesound.org/people/pulswelle/sounds/352058/

Freesound – “Bull Island Seabirds” by iainmccurdy https://freesound.org/people/iainmccurdy/sounds/523914/

Freesound – “waves and wind.mp3” by soundmary https://freesound.org/people/soundmary/sounds/196638/

Freesound – “starting honda.mp3” by amliebsch https://freesound.org/people/amliebsch/sounds/39050/

Freesound – “Celtic Whistle Melody” by f-r-a-g-i-l-e https://freesound.org/people/f-r-a-g-i-l-e/sounds/520148/

Long Road Ahead by Kevin MacLeod is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Source: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-free/index.html?isrc=USUAN1100588

Artist: http://incompetech.com/

Freesound – “Airport Departures Area Ambience” by TwoLivesLeft https://freesound.org/people/TwoLivesLeft/sounds/352685/

Freesound – “Plane taking off.wav” by Santiboada https://freesound.org/people/Santiboada/sounds/348027/