in which we celebrate an arrival and a departure, comings and goings, death and a new life…

in which we celebrate an arrival and a departure, comings and goings, death and a new life…

It’s all good. I’m waiting at the airport for my sister Karen to arrive from Vancouver, just in time for the celebration of life at two o’clock tomorrow afternoon. It’s a flying visit literally, as she used up her holiday entitlement months ago, being here before and after Dad’s death, so this time she’s here on compassionate grounds.

Here she is now…‘Sis!’ ‘How was the flight? ‘Not bad thanks.’ ‘Give me that…’ ‘Alright, hey what’s that? ‘I’m recording your arrival.’ ‘You’re not allowed to do that at an airport.’ ‘I didn’t ask.’ ‘Oh my god.’ ‘You did well to get the time off.’ ‘Yeah, work is crazy and they weren’t too happy.’ ‘Well, you’re here now.’ ‘How are things?’ ‘All good, all organised I think. The cousins are driving up from Devon. Pete’s bringing the King crowd, Pete and Jackie, Gloria’s coming with her man, Jim and his wife, and then there’s the neighbours…’ ‘How many?’ ‘I don’t know. I invited them all.’ ‘You’re not going to record the celebration?’ ‘I thought I might…’ ‘No, I mean you’re NOT.’ ‘Oh.’

I knew she was right, of course. I’d taken a risk framing my father’s passing and my mother’s homecoming as a Celebration of Life when many of the guests would have known the difficulties between my father and I over the years. Folding in the celebration of my mother’s return to her own home with a wake, has no doubt helped to deflect criticism for not holding a traditional church service, cremation or burial, but walking amongst the guests with microphone in hand might be a step too far. So let me tell you briefly how things went down.

As it turned out, the weather was kind and we had a decent show in terms of numbers. With the neighbours, eight or ten of them, a contingent of six family from Ireland and the cousins who drove up from Devon specially. With a few of mum and dad’s old friends and a former work colleague of my father from way back, we had maybe thirty people. My mother was right at the centre of things. She looked fit and fabulous, thanks to the carers, wearing a white linen blouse over a pretty summer dress, a blanket over her knees, and a shawl. I’d put a cork board up in the conservatory with pictures of both my father and my mother pinned to it, some on holidays showing them together and happy, others marking significant moments in the family history, their wedding, my christening, together with some newspaper clippings of interviews he’d done for an airline trade paper.

My daughters moved gracefully amongst the guests with trays of canopés and drinks and the smoke of the barbeque—a bold move I confess—added a festive atmosphere without causing an embarrassing fog. The high point of the afternoon was to see my mother responding to the attentions of those gathering around her. If she appeared a little bewildered from time to time, there were also moments where she smiled and even responded to entreaties and compliments.

It’s quite astonishing how the social function of our brain, the desire, need, to be part of the group, survives the ravages of dementia. The guests, rather marvellously, each took a moment to introduce themselves or remind her of who they were, and there seemed to me to be a genuine kindness and respect in their approach. I’ve no doubt her dementia makes people circumspect, unable to gauge whether indeed she even remembers her husband has died, but it occurs to me this skirting of the issue was no bad thing for day.

I talked about my father with his old friends and colleagues, and with one or two of the neighbours who told stories of him taking a daily constitutional and waving to them as he passed by or stopping to chat. After three or four hours, the guests seemed to leave as one, almost by instinct or through decorum, melting away to their cars and houses and leaving us to clean up.

It was good to see everyone. Good for my mother certainly, but good for me too. Even after just a few weeks alone together, the event and the company came as a relief. And I feel my duty is done. Plus, having my sister here, just a few days, halved the care burden and doubled the time I’ve had outside the home, so providing a break from the routine. Taking her to the airport again so soon after her arrival feels premature and I wish she could stay longer. Ten hours on the plane will cover the five thousand mile journey back to her work and her own life, though I can see she’s struggling with the thought of leaving. Only a year ago, she and her long-term partner, a former paratrooper in the Canadian Airborne broke up. They’d been together for twenty-five years. She’s now living in an apartment, alone, and she’s fallen out of love with her work, too. She wants to be here to help with the care and to be with her mum. She wants to come home. Instead, she finds herself flying away from all she loves.

The garden’s deserted now, just a lot of tables and chairs to be put away. It was hard saying goodbye to my sister, not least because she really didn’t want to go. Hard too, because now the celebration of life is done, it’s business as usual…me and mum alone together. Only there’s someone else here now, maybe because of the celebration. Or maybe because I just haven’t wanted to think about him that much. My Dad. Our Dad. In a word, I guess what I’m feeling is guilt. But it’s more complicated than that, harder to decipher and indeed to tell as a story…so let me tell you about one small incident first…but one that’s stayed with me all week. It was at the Celebration of Life. It started as one of those conversations that’s all about making the right noises. Speaking well of the dead, paying respects, that sort of thing.

I was talking with our Irish cousin, a truly lovely woman, a nurse all her working life, a great mother to five children and a great wife to her doctor husband. She’d known my Dad well when he lived with her family in Ireland as a young man. He was working at Shannon airport and he was maybe ten year older than her, eighteen to her eight. He was obviously a favourite uncle back then, a protector, someone to look up to. I listened. And I hoped she might stop there. But she didn’t. She began to tell me how wonderful my father had been with my mother. How he’d suffered and sacrificed himself to take care of her She came close to canonising him as a saint there and then, as only the Irish can do with their ghosts and priests and demons and heroes, and the words came out of my mouth before I could stop myself. ‘He used to lock mum in her room. He wouldn’t let anyone see her, friends or family.’ ‘I don’t want to hear about that,’ she said. And that small act of denial set me off again. ‘She had bruises. The police were called.’

My cousin, lovely woman that she is, flushed with anger and gain said she didn’t want to hear it. This time I had the sense to let it go. Somehow, the awkwardness passed, someone came over and joined us, I went to get drinks for the guests, I can’t recall now. Certainly, there was no row. When it came to saying our goodbyes, nor was there any lingering resentment on her part, at least as far as I could tell, and only a certain reticence on mine. I’d spoken out of turn and at the wrong time and I regretted that.

I should have kept my counsel at what was after all a celebration of a life, not an inquest, even if I spoke my truth. Because of that indiscretion, because I’m more relaxed with the care, because I’m now alone in the house with my mother, the house she shared with her husband of over fifty years…because I’m living amongst his things, golf clubs in the garage, Constable reproductions on the walls and sleeping in his bed, I can’t help but brood on our relationship, and especially on the harsh judgements I’ve made of his character and behaviour.

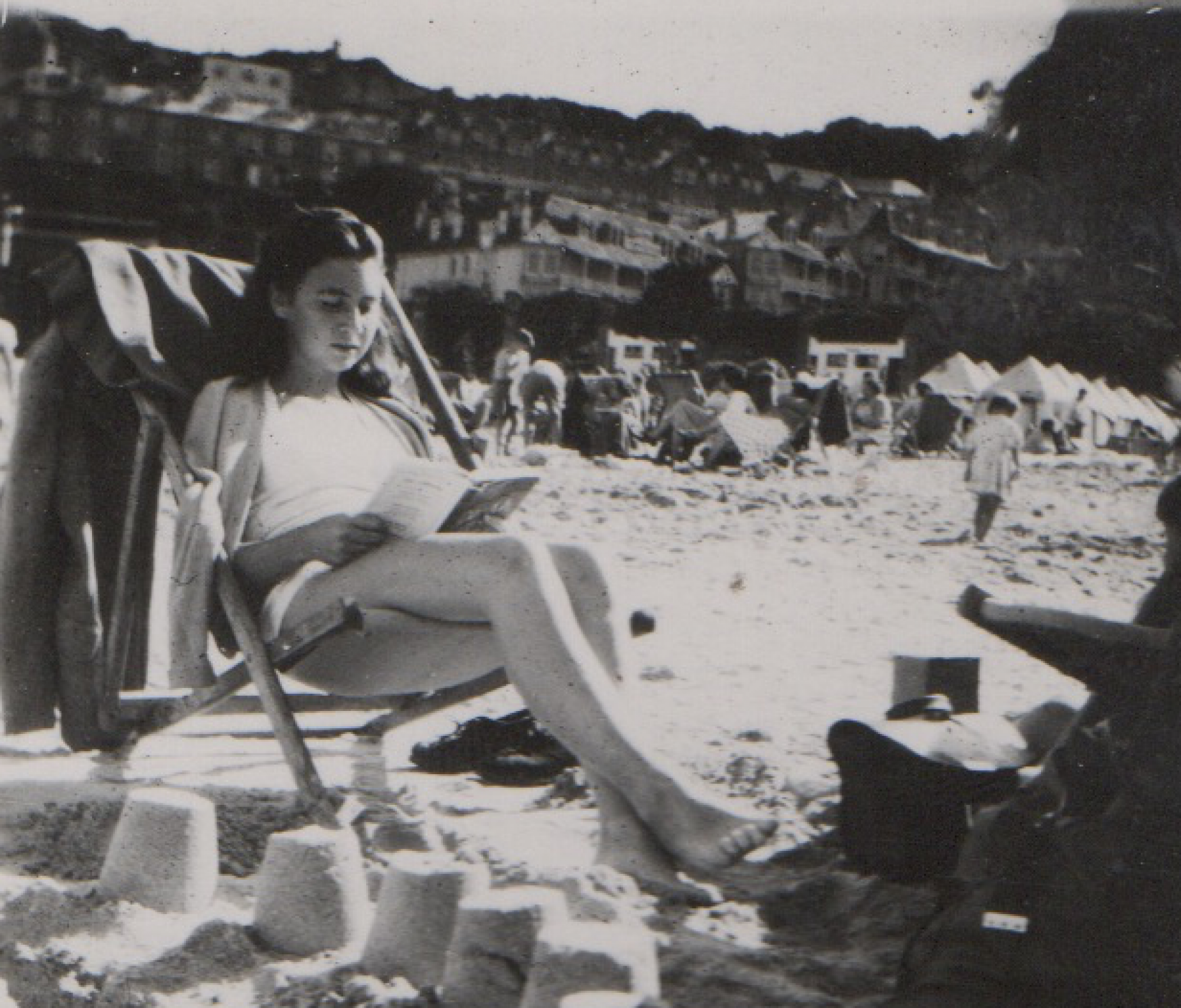

You might remember this from season one… Our relationship was ever awkward and angry. On both sides. Whenever we saw each other, he would offer his hand but could never meet my eyes as he did so. Physical contact of any kind was hard for him. The tables have turned now. It’s me who’s having trouble meeting his eyes. It’s me who’s having trouble reconciling the photographs on the cork board — holding my sister aloft as a child, on a sun lounger with mum beside him, kneeling proudly next to his five year old son who’s wearing a smart suit and looks a lot like Rupert Bear—with my portrait of an abuser. Now, with the photograph albums of the family, many from when my sister and I were young, I see no abuse, no rancour, only a time of innocence.

Do photographs lie? Or does memory? I see smiling faces and a happy family. I see myself in the green strip of my football kit, playing for the local team with my friends, a team he started and managed for us boys. I hear his shouts from the sidelines. When sis was here, we drank wine after the guests had gone and we talked about old times, as you do. One story we both recalled, clear as day. It was Dad sitting at the end of our beds when we were only seven and nine years old, telling us the same spooky tale we demanded of him whenever he was there. Often he wasn’t there, away on business. Sometimes he was not in the mood and was harsh and flicked the lights out with only a few words.

But often, especially after a few drinks, he was kind and soft and sentimental and he’d tell us the story of a fisherman, lost in a storm at sea, who’s beloved stands on a stormy Irish shore calling to her man, Paddy Reilly by name, when he fails to return to her. I only found out recently that the story wasn’t true. I know, because I googled it. There was no fisherman. There was no woman pulling her shawl tightly around herself on a windy shore, though there is a mention of stormy seas and rough waves.

Written in 1912 by a Percy French, the song was inspired, rather unromantically, by the emigration of a local taxi driver to Scotland. The taxi driver used to drive the songwriter about town, but disowned the song that had been written in his name. Of course, there’s nothing unromantic about the Irish as a race and indeed the theme of loss has given the tune a long afterlife in mourning the emigration of so many Irish souls in search of streets paved with gold abroad. Men like my father I suppose.

But whatever about that, my sister and I adored my father’s version, a dark tale told to set the scene before the singing began. As we snuggled under woollen blankets and warm sheets, cosy in a world before duvets, we pictured the low black clouds, the rain and the raging seas, we saw the woman on the lonely strand, looking out to sea, her man lost, her hopes and dreams fading and the wind about her howling. And when my father ran out of lyrics and hummed the tune as he backed out of the room and turned out the lights, we hunkered down in our beds, dreams coloured by the magic tale, glad to be safe from it all.

What does this insistent memory say? Everything and nothing I suppose. Together with the photographs I’ve found of me in my football kit, playing for his team, of my sister held joyfully aloft in his arms, of my parents smiling and sun-kissed on their loungers, it says no life should be reduced to a single story, to a one-sided account that seeks to make a rounded, multi-faceted person into something linear, something simple and straightforward. We all have sides to us, aspects, parts hidden and revealed at different times in our lives, characteristics that show themselves only when circumstances pressure their release. We all feel shame, and joy, disappointment and exaltation. We are all of us many different people to the many different people we encounter in our long lives. My father, I know now, is one such.

Neither Paddy Reilly, nor my father, will ever come home. And yet through song and memory, neither is entirely gone either. The past can be a very private place, a place each of us experiences quite separately from others, even from those who seem to share the memory . And because memory is so partial, so shaded and imperfect, the past is not fixed. It shifts and changes shape, ebbs and flows, people and places morphing like sea mist in front of our eyes, obscuring the true horizon, obscuring our loved ones from us, leaving only shadowy ghosts and isolating us in our own lives somewhere between hope and despair, alone on the shore…